Lead Your Team To Solve Hard Problems, Part II: QMN079

By closely examining the context and defining the problem, the first steps in Operational Design can help set the stage for much more effective planning and execution.

(This week’s report is a 6 minute read)

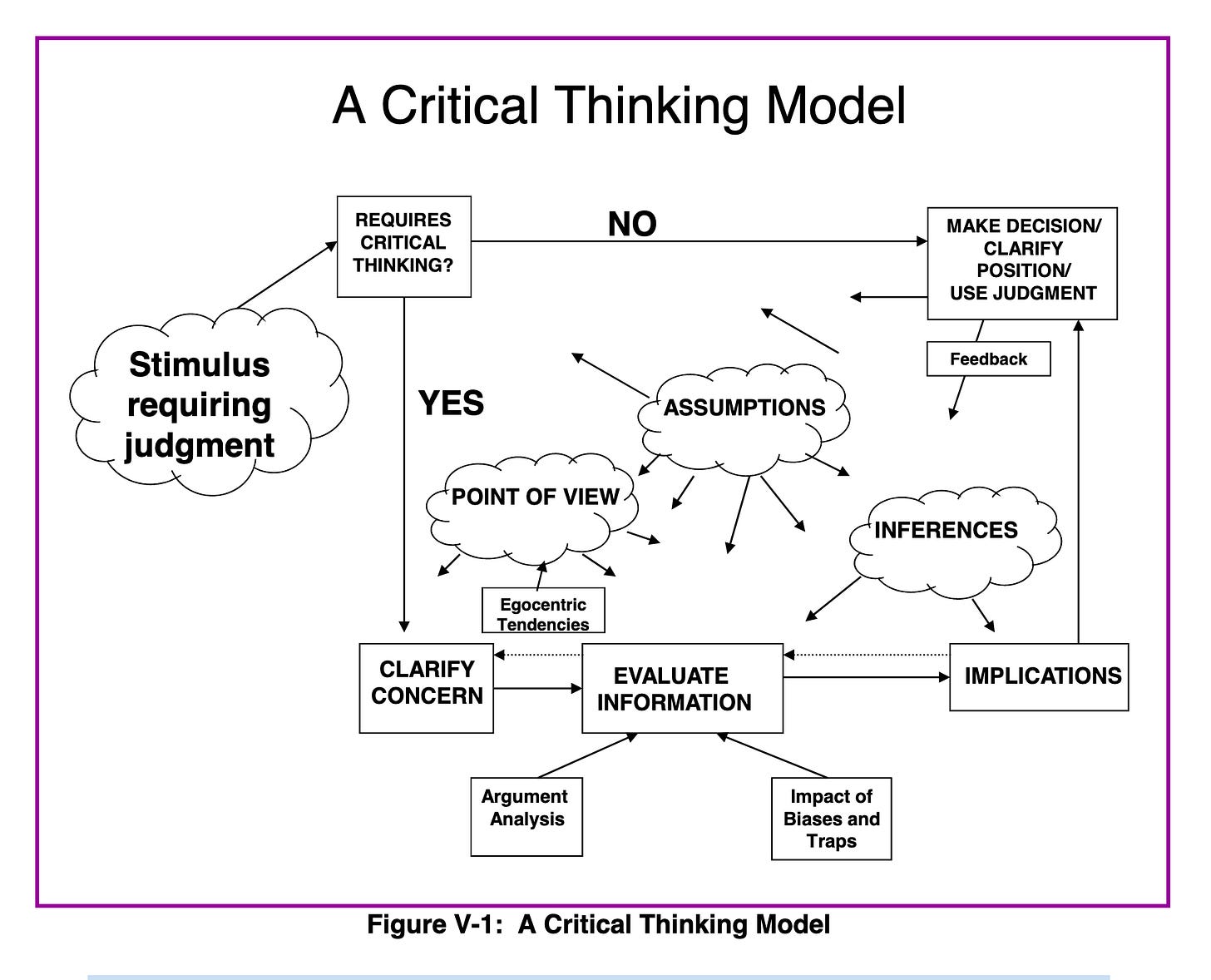

BLUF: By closely examining the context and defining the problem, the first steps in Operational Design can help set the stage for much more effective planning and execution. The US Department of Defense’s Joint Staff has laid out a few practices and concepts that can help guide teams to take these preliminary steps using both critical and creative thinking. We’ve got them, and some sweet diagrams, here.

Brady here. In order to solve new, hard problems, a team needs to fully understand the environment in which the problem must be solved, and honestly and thoroughly define the problem itself. Too often leaders and planners take the operational environment for granted, oversimplifying complex social systems or ignoring their influence altogether. Just as wrongly, problems remain with vague definitions making their solutions equally difficult to define. By applying a few methods and practices appropriately, operational design can help set the stage for more effective planning and execution - and some of the first steps include defining the operational environment and the problem itself.

U.S. special operations forces assigned to the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) maneuver through an urban environment near Aalborg, Denmark, September 5th, 2018. U.S. Army photo by SSG Steven K. Young

“Design does not replace planning, but planning is incomplete without design. The balance between the two varies from operation to operation as well as within each operation. Design helps the commander provide enough structure to an ill-structured problem so that planning can lead to effective action toward strategic objectives.” General James Mattis, 6 October 2009

In the fall of 2011 the US Department of Defense’s Joint Staff published a handbook that explored methods that use critical and creative thinking to understand and describe ill-defined problems and visualize broader approaches to solving them. Expanding upon then-General James Mattis’s 2009 Vision for a Joint Approach to Operational Design, it observed that commanders and staffs generally tend to use standard planning processes mechanically, losing the importance of the underlying creative process by focusing too closely on procedure and details. This handbook identifies a few different aspects of defining the context of problems and problems themselves, which we’ll include here.

From the Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design Version 1.0, 7 October 2011. Tellingly, many of the models in Operational Design are used to facilitate dialogue between the leader and his staff used to characterize the operational environment and what end states should look like.

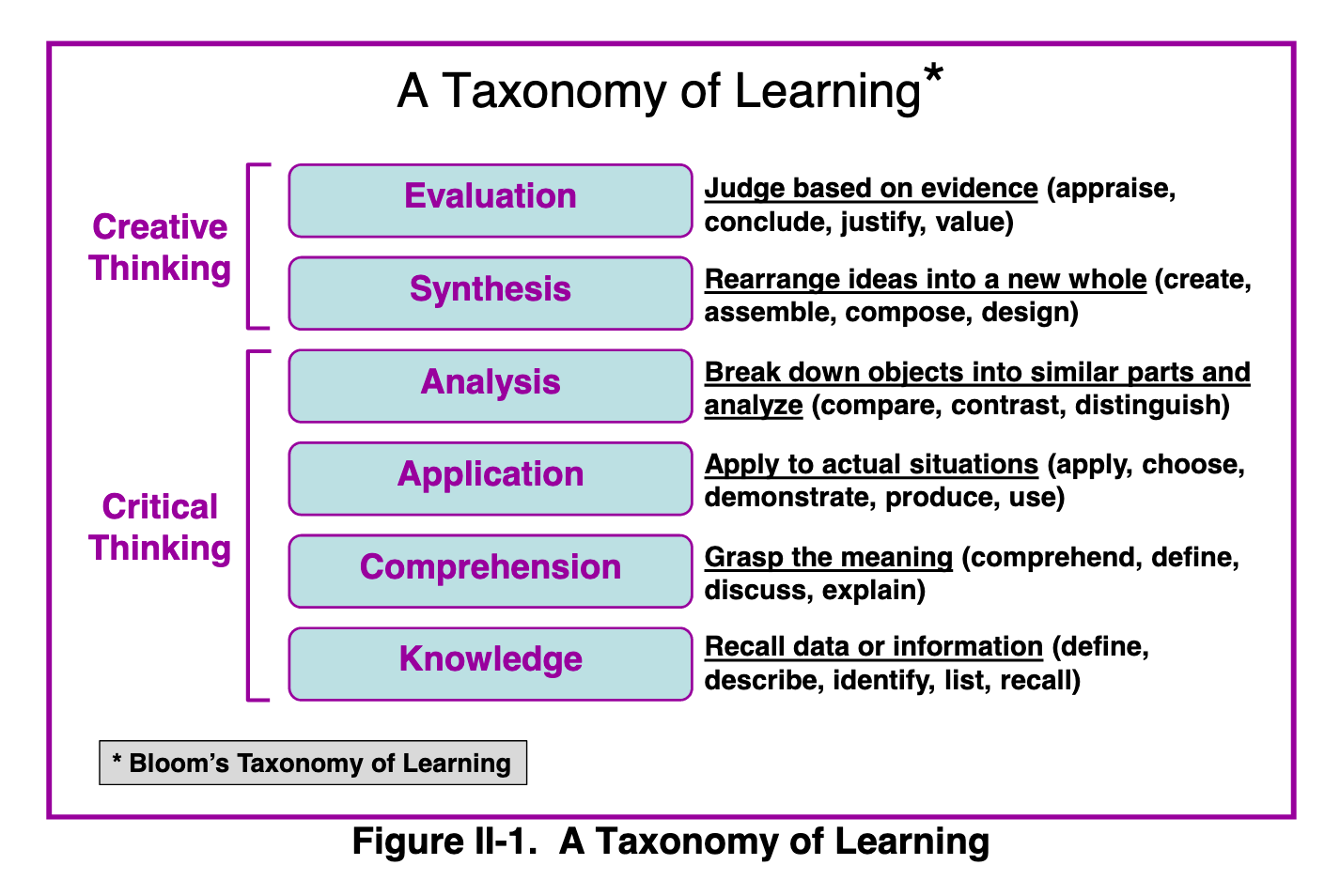

One popular misconception about military planning and communication processes is that creativity isn’t valued in them. This couldn’t be more wrong - in order to define the problem and it’s context, both creative thinking and critical thinking are required. Led by a commander but carried out by the commander’s staff, we can see with the diagram below what actions are considered part of creative and critical thinking overall. Interestingly, much of the creative thinking tasks around evaluation and synthesis are made possible by a senior commander’s training, education, experience, intuition and superior judgment. This model, Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning, was originally developed 60 years ago for educational purposes, but provides a great set of actions required for specific types of thinking.

From the Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design Version 1.0, 7 October 2011

“Creative thought has often counted for more than courage; for more, even, than gifted leadership. It is a romantic habit to ascribe to a flash of inspiration in battle what more truly has been due to seeds long sown, to the previous development of some new military practice by the victors, or to avoidable decay in the military practice of the losers.” Basil H. Liddell Hart, Why Don’t We Learn From History

By using these types of thinking, leaders and staffs need to determine what actions they can carry out. But the first task is to identify the problem’s context - generally considered to be the operational environment. And this is done with a process we presented here in May - the Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Environment (JIPOE) process. The process forces planners and leaders to truly define where they’ll be operating, describe both the environment and the actors within it, and how the actors will behave given the nature of the environment. The result is not just a picture of the environment as it exists, but a consideration of where it’s headed.

JIPOE Process

Once the leader and planners have a good understanding the operational environment - or context- they must define the end state - specifically the desired or intended state of the operational environment. The gap between the operational environment today - or current state - and the desired end state is the definition of the problem. Framing the problem leads to creation of a problem statement - and a good one in broad terms describes the requirements for the transformation from current to desired state and includes expected changes in the operational environment - considering the fact that it’s made up of humans that compete and have tensions within that environment.

From the Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design Version 1.0, 7 October 2011

Operational Design, as it’s been created, is focused on campaigns or major operations, and so the handbook recommends characterizing both the environment and the problem in terms of systems. The idea is to take the current, coherent understanding gained by examining the environment and identify relevant relationships. As most human organizations with independent actors are considered complex adaptive systems, focusing on the relationships as opposed to the entities themselves is important. Defining these key relationships and the entities involved will help the leader and staff to develop objectives that will guide the team to reach it’s desired endstate.

Understanding the context for the problem and then defining the problem in to a problem statement sets conditions for a leader and planners to create relatively simple, straightforward plans that have a greater likelihood for success. In the next post, we’ll get deeper into a few concepts that help a leader determine which parts of the problem to attack and how. (BJM)

*****

SPACE IS BACK: A Small-Rocket Maker Is Running a Different Kind of Space Race (9 min) “Until speaking with Bloomberg Businessweek, Astra, the three-year-old rocket startup behind the test, had operated in secret, rolling nitrogen clouds aside. The company’s founders say they want to be the FedEx Corp. of space. They’re aiming to create small, cheap rockets that can be mass-produced to facilitate daily spaceflights, delivering satellites into low-Earth orbit for as little as $1 million per launch. If Astra’s planned Kodiak flight succeeds on Feb. 21, it will have put a rocket into orbit at a record-setting pace. Chief Executive Officer Chris Kemp says he’s focused less on this particular launch than on the logistics of creating many more rockets. “We have taken a much broader look at how we scale the business,” he says.” (BJM)

WHY WE DO WHAT WE DO: Institutional operating codes: the culture of military organizations (9 min) “The editors present a selective suite of implications. They note the social links from any military to its larger culture, the criticality of military education to sustain critical thinking, and the tensions between continuity and change. Gil-li Vardi's point about the difficulty of leveraging culture is underscored: "organizational culture is a resilient and even sluggish creature, which operates on cumulative knowledge, organically embedded into a coherent, powerful and highly restrictive mind-set." This is the most salient feature of the study, assisting leaders in closing the gap between today's force and one that meets the needs of the future conception of warfare. Murray's past works on innovation clearly show that an organizational culture inclined to test its assumptions, assess the external environment for changes routinely, and experiment with novel solutions is best suited for long-term success. The challenge for leaders today, not explored enough in the book, is learning how to successfully reprogram the internal code to improve its alignment with new missions or technologies. We can hope some enterprising scholars will jump into this field and apply the same conceptual lens to complement this product.” (BJM)

NEW, EFFECTIVE SOPS: Remotely Piloted Aircraft: Implications for Future Warfare (15 min) “The idea of operating RPAs in a flight is still new. Operational planners typically task the closest RPA available just prior to the execution of a complex strike, requiring extensive coordination among the participants. But an RPA flight generates synergistic effects, just like manned aircraft, through a mutual understanding of responsibilities and a shared awareness of the battlespace. This is best cultivated through extensive prestrike planning and briefing, along with real-time information sharing during execution. Bringing together single aircraft from separate squadrons just before a mission ignores the lessons of airpower history in the name of convenience.” (BJM)

Remarks Complete. Nothing Follows.

KS Anthony (KSA) & Brady Moore (BJM)