Memorial Day: QMN023

I didn’t think much about Memorial Day for most of my life. This changed for me in the past 12 years because I had a good friend die in Iraq in 2006.

(Today’s report is a 7 minute read)

Today’s Quartermaster is a special Memorial Day edition. We’ll be back on Tuesday, 28 May. Enjoy the holiday.

Brady here. I didn’t think much about Memorial Day for most of my life. This changed for me in the past 12 years because I had a good friend die in Iraq in 2006.

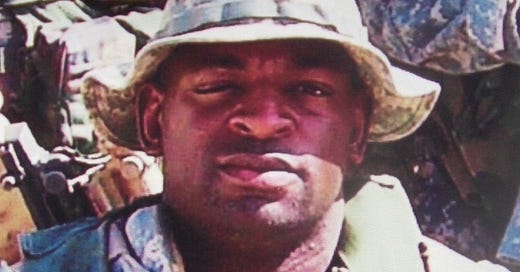

The man that died was Staff Sergeant Dwayne Lewis. “Lew”, as he was known to hundreds of infantrymen in the 10th Mountain Division, was first one of my Fire Team Leaders in Afghanistan and then one of my Squad Leaders in Iraq. Lew was originally from Grenada and grew up in Brooklyn. Lots of people who’ve served know of someone they served with who says that if they hadn’t joined the military they’d either “have wound up dead or in jail” - that was Lew. I’m pretty sure he boosted a few cars in his youth, and I know he’d busted a few heads.

He came to my platoon in 2003 as a Sergeant (E-5) as we headed to Kandahar - he stood out immediately because as an amateur bodybuilder he was likely the biggest guy in our battalion of about 500 men. That’s a pretty important thing for sergeant in an infantry battalion, so he was automatically a great example for the three soldiers he led. He was a stoic guy most of the time - he never wasted a word - but could be pretty funny when there wasn’t work to be done. In Afghanistan in 2003 and 2004 our platoon flew all over looking for Al Qaeda to fight as the new government tried to build its internal security forces and take control of the country. Lew kept a real focus on the mission, knew his strengths and weaknesses, and took care of his soldiers and kept them on task - a very good junior noncommissioned officer (NCO) by anyone’s standard. We spent time together on the sides of mountains in the north and in dusty desert villages in the south. We searched a lot of homes looking for weapons and signs of Taliban presence. We slept on the ground, frequently ran low on food and water, and walked up and down mountains and valleys for days. I never heard Lew complain, but I knew that when our missions lasted longer than a few days he got irritated that he was missing gym time. He was often recognized by the company commander or battalion commander for his leadership capability and example.

Our battalion came home after nine months and immediately started training to go to Iraq. Lew got recruited by the battalion’s scout platoon, got promoted to Staff Sergeant (E-6), and took over a squad (eight men) of snipers and spotters. Right before we shipped to Iraq I also came to the Scout Platoon as the platoon leader. In West Baghdad and the city of Abu Ghraib, the scout platoon overwatched key parts of the city for insurgents emplacing improvised explosive devices (IEDs) meant to attack Iraqi security forces and us. I spent some hot days in hides across the city with Lew - he had grown as a leader and it was good to work with him again. Within a few months I had to leave the platoon leader role to fill a battalion staff position but Lew stayed with Scouts. He led daily patrols across our area, keeping key areas safe for US and Iraqi forces as the country got deeper into internal fighting.

In January 2006 Lew came up to the battalion headquarters one day and asked me to reenlist him. Reenlistments are a big deal for soldiers and NCOs - they’re essentially re-committing themselves to another contract with the military and do so with a sworn oath - the same one they originally enlisted with. I was honored to be asked - a guy as notable as Lew could have asked the Battalion Commander but instead he chose me. He was a humble guy and instead of calling out a crowd to watch we just stepped outside, swore the oath, signed and shook hands and went back to work. That’s the kind of guy he was - for his size & strength he was a celebrity in and out of the battalion, but chose to make no fuss and just get on with it.

About a month later in late February our part of Iraq became very tense because Sunnis and Shias were on the verge of civil war - the golden dome of the Shia al-Askari Mosque had been destroyed by several, presumably Sunni, insurgent IEDs and there were retaliatory killings going on nightly by the thousands. American early morning patrols would come across hundreds of bodies of people who were pulled from their homes, lined up and shot during the night. Our part of town had Sunni blocks next to Shia blocks, so men were standing on rooftops armed, waiting to defend their families if attacked. One evening Lew and other parts of the scout platoon were searching for a kidnapped American journalist named Jill Carroll in the rural areas north of Abu Ghraib. They surrounded a house where she was suspected to be held, and one of the men guarding the home mistook the scout platoon for a sectarian attack - and shot at a silhouette in the dark. Lew hit the ground and when the shooter realized who we were he immediately surrendered and pleaded that he was unaware. Lew was shot in the neck so badly that he bled out in just a few minutes, despite having some of the battalions best soldiers trying to stop the bleeding. He died in the arms of one of his best friends while the MEDEVAC helicopter was landing. He was flown back to the airfield and was pronounced dead there.

I stayed up almost that whole night stunned -because of his strength and size and popularity he was the last guy you thought would have been killed. It sounds dumb because death doesn’t care about all that, but that’s the way your mind thinks. I wrote a letter to his mother, and got to meet his family when we came home five months later. His remains are at Long Island National Cemetery in Farmingdale, NY. Section A1, Row A, Site 61. When I visit, I usually buy a protein shake and leave it there - when he lived you never saw him without it.

So now on Memorial Day I think about Lew. I think about the things he said, what it was like being around him, what he died for - and what he knew he was risking. Lew wasn’t a particularly patriotic guy, but he was like a lot of guys I served with - happy to have the opportunity to do the job of a soldier and lead soldiers, to carry a rifle, to stand for something and have a purpose - in a world where it seems like it can be hard to find one today. With as professional and self effacing and disciplined as Lew was, it still seems unfair that his life ended there and I’m still here.

We’re fortunate to have men like Lew serve us and accept the risks. We should honor him and the rest with the hope that we always will. And we should work hard to deserve it. (BJM)

This story originally appeared in a Memorial Day Newsletter for the IBM Corporation’s Federal Group in Herndon, Virginia in May 2018.

SCHEDULED REMEMBRANCE: The Evolution of Memorial Day (3 min) “The success of the occasion did so much toward softening the bitterness remaining from war days that immediately following it plans were discussed for a permanent Memorial Day to be held each year. The 30th of May was tentatively agreed upon. It was more suitable because in the late spring a greater quantity of flowers would be in bloom.” (BJM via @paryshnikov)

"Let us, then, at the time appointed, gather around their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with choicest flowers of springtime; let us raise above them the dear old flag they saved from dishonor; let us in this solemn presence renew our pledges to aid and assist those whom they have left among us as sacred charges upon the nation's gratitude—the soldier's and sailor's widow and orphan."

– John A. Logan, commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, on the first Memorial Day, 1868

KSA here. In thinking about what to write for Memorial Day, I struggled with a couple of different psychological obstacles, primarily my relative emotional distance from the day's meaning. Unlike those who have lost friends, comrades, brothers, spouses, or children in combat, I don't shoulder any personal sense of grief that remotely resembles the vacuum of absence that I have observed in my warfighter friends, in spouses who've been handed a neatly folded flag and left adrift, or in those who've grown up in the shadow of a parent gone forever.

I am well acquainted with grief and the shock of sudden death, yes, but I don't think it analogous to the social and psychological complexities that come with a day that is set aside for those who've been slain in war. Death is death and grief is grief, but not all death and grief are equal: some are built on tragedies that cannot be comprehended; reminders of our fragile and fleeting existence, of the time we do not have and can never have back.

As a writer, I often think I should have more to say. Today, at least, I do not. Instead I'll raise a drink to those who can't: they are better memorialized by better writers than me.

Move him into the sun—

Gently its touch awoke him once,

At home, whispering of fields half-sown.

Always it woke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.Think how it wakes the seeds—

Woke once the clays of a cold star.

Are limbs, so dear-achieved, are sides

Full-nerved, still warm, too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

—O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth's sleep at all?– Wilfred Owen

Remarks Complete. Nothing Follows.

KS Anthony (KSA), Chris Papasadero (CPP) & Brady Moore (BJM)