(This week’s report is a 10 minute read)

BLUF: Some of the best graphic representations of information and processes are military in context. The span of control and influence in military situations is so broad that many systems across many environments have a bearing upon success within a given command. The need to understand how each system influences every other can be very real - time, location, domain (sea, air, land, space, cyber, information, cognitive) all play a role in success or failure. Does being able to express complex problems and solutions graphically make it easier to identify and accomplish meaningful goals?

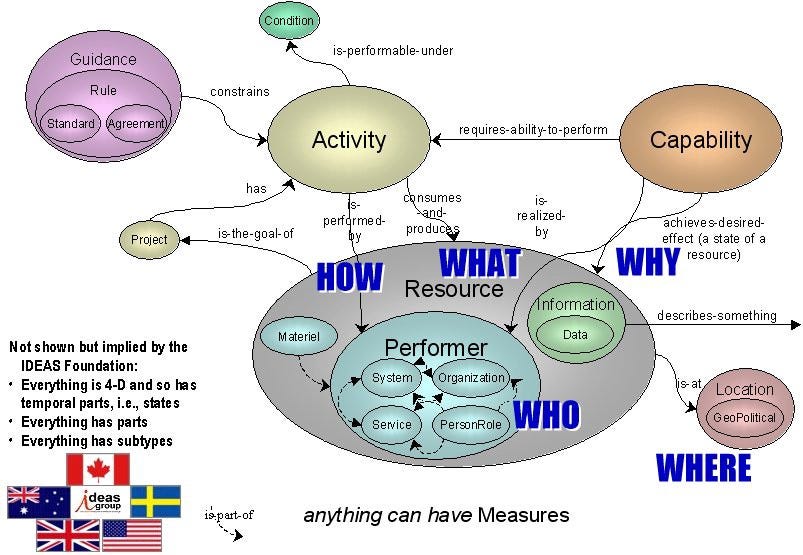

Brady here. In 2014 Postlight founder & CEO Paul Ford posted a Medium article called “Amazing Military Infographics” where he confessed his love for US Department of Defense (DoD) PowerPoint diagrams. In particular he cited the impressive mandate of the DoD Architecture Framework (DODAF):

“If you want to develop an architecture, this is your framework—an abstraction specifically designed for manufacturing abstractions. Here’s one way to look at it:”

“Take some time with that graphic. After a while you realize that this image could be used anywhere in any paper or presentation and make perfect sense. This is a graphic that defines a way of describing anything that has ever existed and everything that has ever happened, in any situation. The United States Military is operating at a conceptual level beyond every other school of thought except perhaps academic philosophy, because it has a much larger budget.”

Ford’s interest made me realize that despite all the many ways modern militaries fail at information technology, some of the best representations of information and processes are military in context. The span of control and influence in military situations is so broad that many systems across many environments have a bearing upon success within a given command. The need to understand how each system influences every other can be very real - time, location, domain (sea, air, land, space, cyber, information, cognitive) all play a role in success or failure.

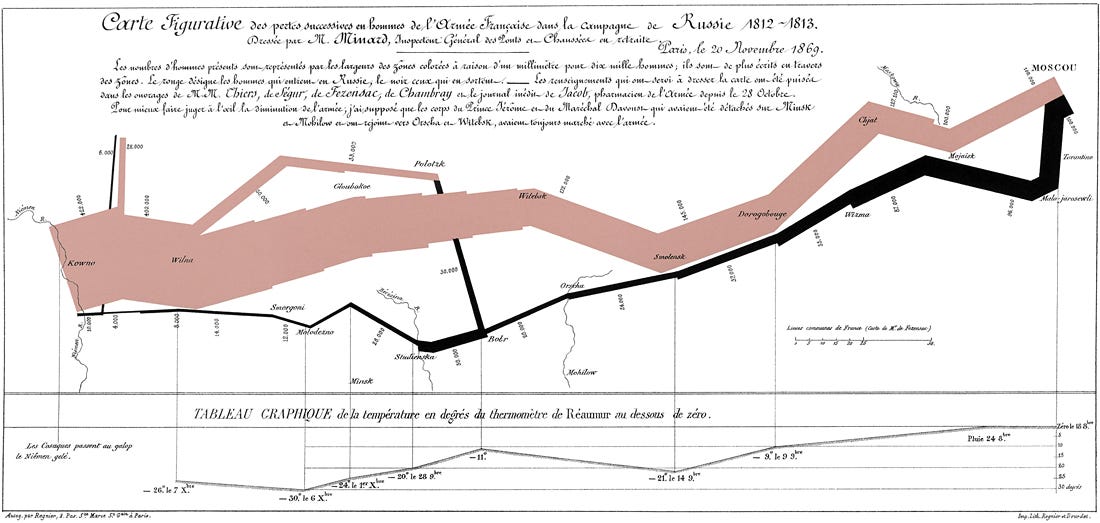

Probably nowhere is this more apparent than an infographic from 150 years ago - Charles Minard’s depiction of Napoleon Bonaparte’s disastrous incursion into Russia in 1812. Edward Tufte himself in his book Beautiful Evidence called it “one of the best statistical graphics ever” and explains all the information it conveys in one shot, as well as what it leaves out:

”Minard delineates the war of 1812 by means of 6 variables: the size of the army, its two-dimensional location (latitude and longitude), the direction of the army's movement, and temperature on various dates during the retreat from Moscow. These 6 dimensions are shown with distinct clarity. There is no instruction manual, nor a jargon fog about a spatial-temporal hyper-space focus group executive dashboard web-based keystone methodology. Instead it is War and Peace as told by a visual Tolstoy.”

Would Minard’s depiction be so masterful without the need to see all the variables together in one image? Military decision making happens amid a never-ending quest for certainty - It’s the need to understand a lot of information across many different systems and how it all interrelates that drives the need for depiction like this. The perception-comprehension-projection model for situational awareness we posted about back in May is a big factor here.

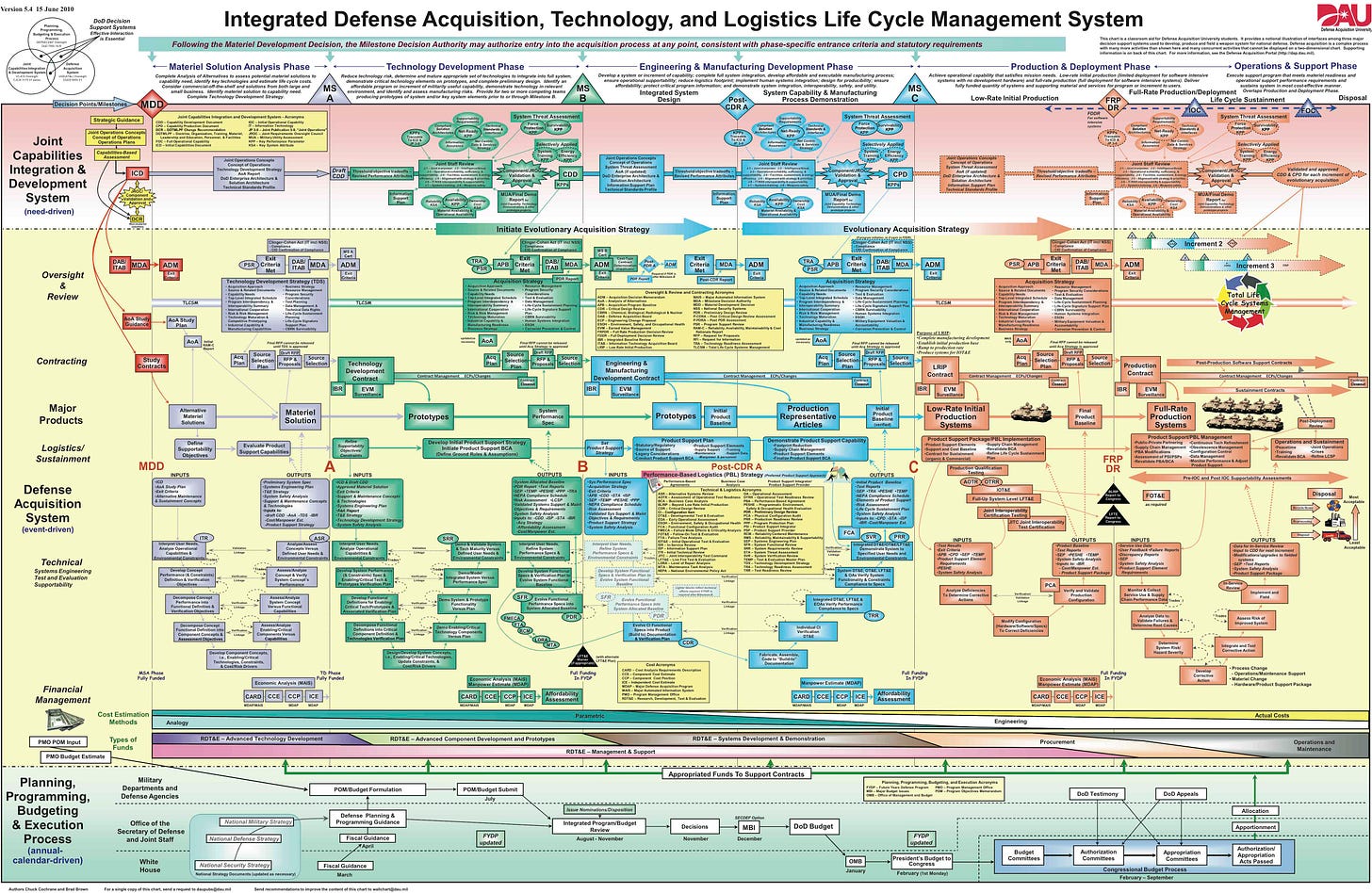

And though the death of hundreds of thousands due to starvation, disease, exposure and trauma is a tragedy, so is the bureaucratic process atrocity depicted in this graphic generally attributed to the Defense Acquisition University.

Lampooned briefly by Noah Schachtman at Wired back in 2010, the defense acquisition struggle remains real to this day, and has caused the US Army to create a whole new 4-Star command (a BFD in DoD) with offices in Austin, DC and NYC to try to circumvent or otherwise fix the multi-year process required to buy technology both innovative and mundane. The graphic is effective - it communicates every painful detailed step in the process, as well as provides the sensation of someone standing on your chest if your job was to try to bring contemporary, SaaS-based AI solutions like Watson to US servicemembers deploying to Afghanistan, Africa and Iraq every month. As you can imagine, a behemoth like this process controls billions of dollars annually and has hundreds of thousands of jobs tied up - so fixing it despite decades of outcry has been nearly impossible.

Finally, late last year I shared a graphic with SFA NYC president Chris Papasadero that explained the crises that western militaries face today after decades of fighting transnational terrorism while Russia and China build technologies, strategies and tactics to defeat them.

We marveled at how different graphic explanations can be between our old world of the deployed US Army and our current world of civilian work. How many of us in the civilian world can express our business problems - much less our planned solutions - with diagrams that address the physical world, time, politics, the internet, navigation, advanced weapons and outer space? Does being able to express complex problems and solutions graphically make it easier to identify and accomplish meaningful goals? Maybe bigger and more complex problems just make for more impressive graphics.

*****

ARMY AVIATION AARs by Pete Wright

Pete Wright is one of my oldest friends and perhaps more versatile than anyone I know. An AH-64 Apache pilot with service in Iraq, and then instructor pilot for the South Carolina Army National Guard, Pete’s also held roles in operations, logistics and intelligence. Along with his wife LeeAnn, Pete also owns and operates Crossfit Rivalry in Columbia, South Carolina. In his spare time he’s an operations leader in manufacturing, and is a recent graduate of Georgia Tech’s Masters in Manufacturing Leadership program. He’s been a Quartermaster reader from the very start and some of our discussions about how seriously US Army Aviation takes AARs and Lessons Learned led me to ask him to share it all with you.(BJM)

Pete here. Army Aviation decisions have life and death outcomes. One wrong decision might cost the aviator and/or the co-pilot and passengers their lives. As a result, aviation units adhere to stringent processes to assess performance, implement corrective actions, and monitor changes through direct leadership involvement. The hierarchy of these after-action reviews (AARs) begin at the crew and team level, through the platoon and company, and eventually impact the battalion and brigade. A unique aspect of military aviation is that a seemingly small event, involving only one crew, may impact all aviation operations across the entire US military. Military aviation is an “Antifragile” system - a term coined by author Nassim Nicholas Taleb, meaning that aviation is a profession that learns from the errors made within and strengthens itself as a result. Aviation AARs represent a tool created from necessity and implemented with high returned value to the organization. I’ll explain it briefly here.

START SMALL: The initial information gathering begins at the crew level. The pilots and other crew members meet at the end of each flight and follow a predetermined debrief format to document critical information about their flight. This debrief focuses on information related to the maneuvers conducted by their specific aircraft. The crew notes areas they can improve, as well as what went well during the flight. The primary focus is on improvement, but positive feedback of a job well done receives some attention.

EXPAND LESSONS LEARNED AND APPLY THEM: The crew then meets with their larger group - the platoon and/or company - to compare notes and prepare to review the mission aspects of their flight from a higher level. This next AAR focuses on the collective needs for improvement of the larger group. The details now include how well the mission was planned, executed, and whether it was successful. This larger AAR is led by company leadership, and supported by individuals specifically responsible for standardization, tactical operations, maintenance, and safety within the company. This group of individuals functions as aviators on missions, but also specializes in improving, maintaining, and monitoring procedures unique to their specialty. The information gathered during this AAR becomes the baseline for updated standard operating procedures (SOPs) designed to mitigate risk and improve performance of the company. Once an SOP update occurs, standardization pilots - experienced aviators with a mandate to take lessons learned and apply them across the organization - develop written tests and conduct check rides in the aircraft with each crewmember to ensure the company follows the guidelines established by the new changes.

Larger missions require additional AARs. These higher level AARs take place at the battalion and brigade level, and higher level leadership and specialized support staff attend. They focus on larger tactical and strategic impacts of the mission but follow a similar format. Quality improvements identified and developed at the lower levels of the hierarchy are discussed and if applicable added to the higher-level SOPs. Once this type of change is made, all subordinate units incorporate the changes into their SOPs.

THIS IS ABOUT PEOPLE & CULTURE: The participants of each level’s AAR understand the purpose and necessity of these events and use transparency and honesty for best results. Individuals often receive constructive criticism, and mistakes are discussed in detail, so everyone understands why an event occurred and how to avoid making the same mistake in the future. The criticism can be hard to hear, but participants recognize the value of the feedback. These AARs begin in flight school, and by the time a crewmember reaches a unit, they already have practice receiving and giving constructive feedback. The culture surrounding AARs begins the first day of flight school and continues through retirement.

After-Action Reviews serve a vital purpose for military aviation. The concept is not complex, but the impact they have on complex systems is significant. These debriefs and reviews gather knowledge and the aviation culture provides processes to improve the organization through effective use of this knowledge. A wise adaptation made by a single crewmember might become military doctrine as a result of the AAR process. The format provides a way to link the intelligence of the entire aviation community, and in turn provides a way for the community to continuously improve and protect itself. (PCW)

******

BOOK REVIEW: THE WAR OF ART by Steven Pressfield

Brady here. If you’ve ever heard someone refer to apathy or writers block as “The Resistance” anytime since 2002 - The War of Art is where that idea came from. Steven Pressfield, the author of the book The Gates of Fire (probably the single most widely read piece of fiction in all the US military in the past 2 decades), wrote the War of Art in order to compile all the advice he gave to aspiring first-time writers who wanted to do what he’s done. His first and biggest step personally was overcoming self-doubt and apathy in order to get the work done and get it to an editor. He takes a military-ish approach to the struggle of productivity and comes out with some interesting perspectives.

Steven Pressfield graduated from Duke University in 1965 and joined the Marine Corps the following year for a short time. In the years that followed, he worked as a copywriter, teacher, mental hospital attendant, tractor-trailer driver, bartender, fruit-picker, and screenwriter. As a screenwriter he ended up homeless living out of a car in Los Angeles while his work was rejected time after time. He finished The Legend of Bagger Vance and was published in 1995 (it came out as a movie in 2000). In 1998 he finished The Gates of Fire, a novel about the battle of Thermopylae from the Spartan perspective, and became a household name among machine gunners and fire team leaders from Camp Pendleton to Fort Bragg.

Pressfield characterizes apathy and self doubt as an innate force against success called “The Resistance”. Everyone has this anti-daemon within them that wants to be unsuccessful and will lead people to unfruitful activity no matter what. With a ton of credibility he explains how he lost against The Resistance for many years and finally found out how to overcome it - temporarily. He explains that the fight against the Resistance is a daily act even for him, but can be won repeatedly if the writer begins to consider themselves as a professional and behave in a professional manner - not taking failures or rejection personally, but as learning opportunities to get better at a craft. Across about 150 pages he communicates these ideas in aphorisms that go from a page to about 4 pages - so it’s a pretty quick read.

I appreciated The War of Art because it’s what I wish I could get from a lot of successful people I admire - a succinct explanation of what they’ve learned about how to to their job well on a personal level. Pressfield failed for a very long time before he succeeded, so he has a lot of stories to tell about what didn’t work and why. He lays out all the excuses and mistakes he’s made over the years and then presents the perspective it’s given him about work, will and resolution. He’s a classicist at heart so there’s a lot of talk about “The Muse” which was a little goofy for me, but inspiration can be important - and Pressfield explains that you find inspiration once you sit down and actually get to work, not when you’re doing something else in order to avoid the work. The book is a bridge between martial ideas and creative ones - and for that it’s rare and valuable. But I’d recommend it to anyone who’s involved in the craft of writing or really anything creative at all - it’s a perspective you’re not going to get anywhere else. (BJM)

*****

WHERE IS THIS HEADED?: Is Our Fear of Smartphones Overblown? (2 min) “During interviews for Digital Minimalism, I’m frequently asked whether I think our culture’s concerns about new technologies like smartphones and social media represent a fleeting moral panic. The argument goes something like this: There are many technologies that were once feared but that we now consider to be relatively tame, from rock music, to the radio, to the telegraph famously lamented by Thoreau. Isn’t our concern about today’s tech just more of the same?” (BJM)

APPLYING LESSONS EVERY DAY: The Spy Who Came Home (40 min) “Georgia’s law-enforcement-training program does not teach recruits to memorize license plates backward in mirrors. Like many of Skinner’s abilities, that skill was honed in the C.I.A. He joined the agency during the early days of America’s war on terror, one of the darkest periods in its history, and spent almost a decade running assets in Afghanistan, Jordan, and Iraq. He shook hands with lawmakers, C.I.A. directors, the King of Jordan, the Emir of Qatar, the Prime Minister of Singapore, and Presidents of Afghanistan and the United States. “I became the Forrest Gump of counterterrorism and law enforcement,” he said, stumbling in and out of the margins of history. But over the years he came to believe that counterterrorism was creating more problems than it solved, fuelling illiberalism and hysteria, destroying communities overseas, and diverting attention and resources from essential problems in the United States.” (BJM)

STAY PREPARED: What Every Man Should Know About Having a Heart Attack (11 min) “Every year in America nearly 800,000 people have a heart attack — and the majority of them are men. Heart attacks most commonly occur in patients with some form of heart disease. Heart disease (a term encompassing several conditions) is one of the leading causes of death in the United States, with more than 600,000 deaths per year, and most of these are a result of heart attacks and strokes. With statistics like these, it is very likely that you or someone you know has been or will be affected by a heart attack. A heart attack may result in sudden cardiac arrest, where the heart stops beating, but most heart attacks are survivable. The good news is that with a little education you can recognize the signs, symptoms, and risk factors of a heart attack, as well as what to do if you, or someone around you, has one.” (BJM)

Remarks Complete. Nothing Follows.

KS Anthony (KSA) & Brady Moore (BJM)