Examining Future Urban Conflict: QMN058

Martial Mental Models: The Quartermaster, Tuesday, 3 September

(This week’s report is a 12 minute read)

NOTE- It’s a short week so we’ve got a short report - just KS and I with a two interesting topics. More of the usual format next week.

BLUF: Megacities - built-up urban areas with a population of 10 million or more - are rapidly becoming more common around the world, and are expected be the setting for a major conflict within the next 20 years. Considering that massive cities of this size are a relatively new feature of human progress, the nature of conflict there is likely to be different from what western armies have prepared for. In an effort to fix this, the US military has been studying the problem for the past few years - I’ll give you a taste of what’s interesting.

Brady here. For the past several years the US military’s been examining the likelihood and character of a future war in a megacity - defined as a built-up urban area with a population of 10 million or more. Last year the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ Population Division noted both the increasing number of megacities and larger share of the world’s population residing within them, saying that,

“In 1990 there were 10 cities with more than 10 million inhabitants, hosting 153 million people, which represents less than 7 per cent of the global urban population. Today, the number of megacities has tripled to 33 […and] the population of megacities has grown to 529 million, and they now account for 13 per cent of the world’s urban dwellers.”

A good amount of these cities are in Asia - including the largest of among them. Also from the UN:

Tokyo is the world’s largest city with an agglomeration of 37 million inhabitants, followed by Delhi with 29 million, Shanghai with 26 million, São Paulo and Mexico City with 22 million each […]Furthermore, Cairo, Mumbai, Beijing and Dhaka all have close to 20 million inhabitants.

With the increasing number and share of the population that today’s megacities represent, the likelihood of combat within one in the next 20 years is only going up. When you consider the advantages that urban environments provide those fighting large, advanced western armies, the likelihood gets even greater. In an effort to prepare for this new kind of conflict the US military’s commissioned a few studies of past urban conflicts and outlined some of the challenges US forces are likely to face.

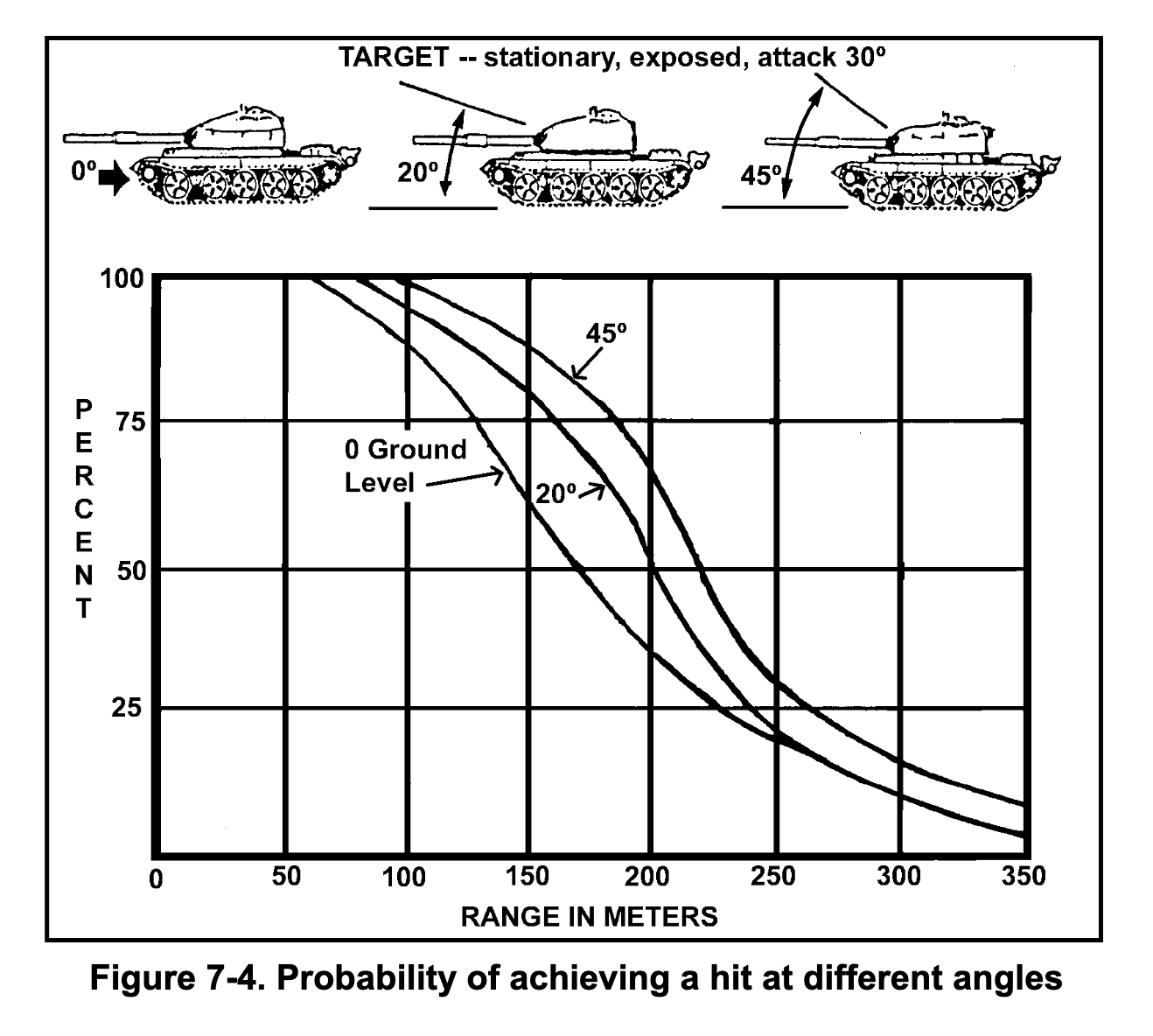

Three-dimensional combined arms conflict

The US Army’s manual for urban combat, Field Manual 3-06.11, Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain (from which the image above comes) lays out across over 600 pages the many tactical and operational considerations that go into urban warfare, but not many of the strategic, big picture ones that seem to cause US forces to stumble so often. Our equipment and strategies simply aren’t made for this fight. Every urban battle is unique, but all have considerations in common that make urban conflict much more deadly for all involved. Population density and structural density make the chance for collateral damage and more second- and third-order effects much greater, and the geometry of combat engagements much more complex. Today much of conventional military equipment is designed to be used in most open areas with opportunities for greater dispersion and standoff because of the maximized lethality of our weapons - for example a 155mm high explosive artillery round has a kill radius of 50 meters, meaning that if it lands within 50 meters of you, it’s curtains. Lots of existing military practices take this type of thing into account to ensure that people and vehicles are dispersed enough that they don’t make an enticing target. Much of this math goes out of the window in an urban environment where close-in high-rise buildings make dispersion hard to achieve. It also means in many cases you’ll need to get pretty close to engage your target discriminately - exposing your force to more danger.

A big part of these changed mechanics is the fact that a megacity will have many surfaces where movement and fire will take place. Subways, sewers and utility tunnels will allow for undetected movement and even massing of forces, while large structures will provide seemingly infinite angles of attack. Think of Blackhawk Down-type ambushes, but at the scale of 20- and 30-story buildings in a city like Dhaka. Consider on top of all this the communications and navigation problems that we all know and love in big cities like New York and you’ve got a recipe for chaos for today’s forces. The question is: how do you plan for and manage a battle within a city like this? How does an individual and an organization gain and maintain situational awareness?

Highly Integrated vs. Loosely Integrated cities

Some cities are more dangerous than others. The ability for a city to bounce back from a disaster is perhaps the most important factor when preparing for and executing military operations there. The Chief of Staff of the US Army’s Strategic Studies Group, in their 2014 white paper (PDF), identified a typology, illustrated in the image above, within which most megacities can be examined. Megacities like Dhaka in Bangladesh and Lagos in Nigeria are categorized as “Loosely Integrated” meaning that they suffer from poor governance, strained flow systems (electric, water, sewage, transportation, and communications) and failing infrastructure that make recovering from natural or man-made disasters extremely difficult. A devastated sewage system without high-functioning and fully-funded public services can lead to widespread deadly diseases in a matter of days for a massive population. Contrast that with a “Highly Integrated” megacity like New York City, with redundant systems, hierarchical government and commerce structures, abundant resources and international connectedness - when New York City experiences a disaster (think of 9/11 or Hurricane Sandy, most recently) it recovers and rebuilds stronger than it was before the disaster.

Knowing what’s at risk for a people and a place are very important for determining risks and goals across a large operation. The US has made more than its share of mistakes by ignoring second- and third-order effects and long term, seemingly “non-military” problems around the world in the past couple decades - it’s refreshing to see them take the bigger, long view for once. But in practice, US forces will need to guard and support critical infrastructure and work to improve governance in these areas while it’s fighting - something it certainly hasn’t mastered in recent years.

Changing needs for intelligence

Human Intelligence or “HUMINT” has been a major focus for the US in the conflicts of the past couple decades, and rightly so. This includes information gained from paid sources - much like confidential informants are used by law enforcement in criminal law. If your aim is to disrupt and disable a transnational terrorist organization and its offshoots, human intelligence is where the best information lies. The problem with HUMINT and combat in a megacity is that it takes too long. There’s not enough time to vet and corroborate the claims of sources when there’s a growing riot or an armed revolt in a dense section of a megacity.

What there will be, and in many cases already exists, are networks of cameras and sensors across the city for purposes like law enforcement, security, utilities, transportation and communications that can be tapped for knowledge of what’s going on and where. The problem is that it’ll come in immeasurable amounts - more than a team of intelligence analysts can handle in a reasonable amount of time. Machine Leaning and AI tools will need to be used to help sift and identify critical information in time to make a difference to operations. Speed in finding problems will be so critical that using predictive models will be required in order to understand the megacity and manage day-to-day operations.

Shrinking the Problem

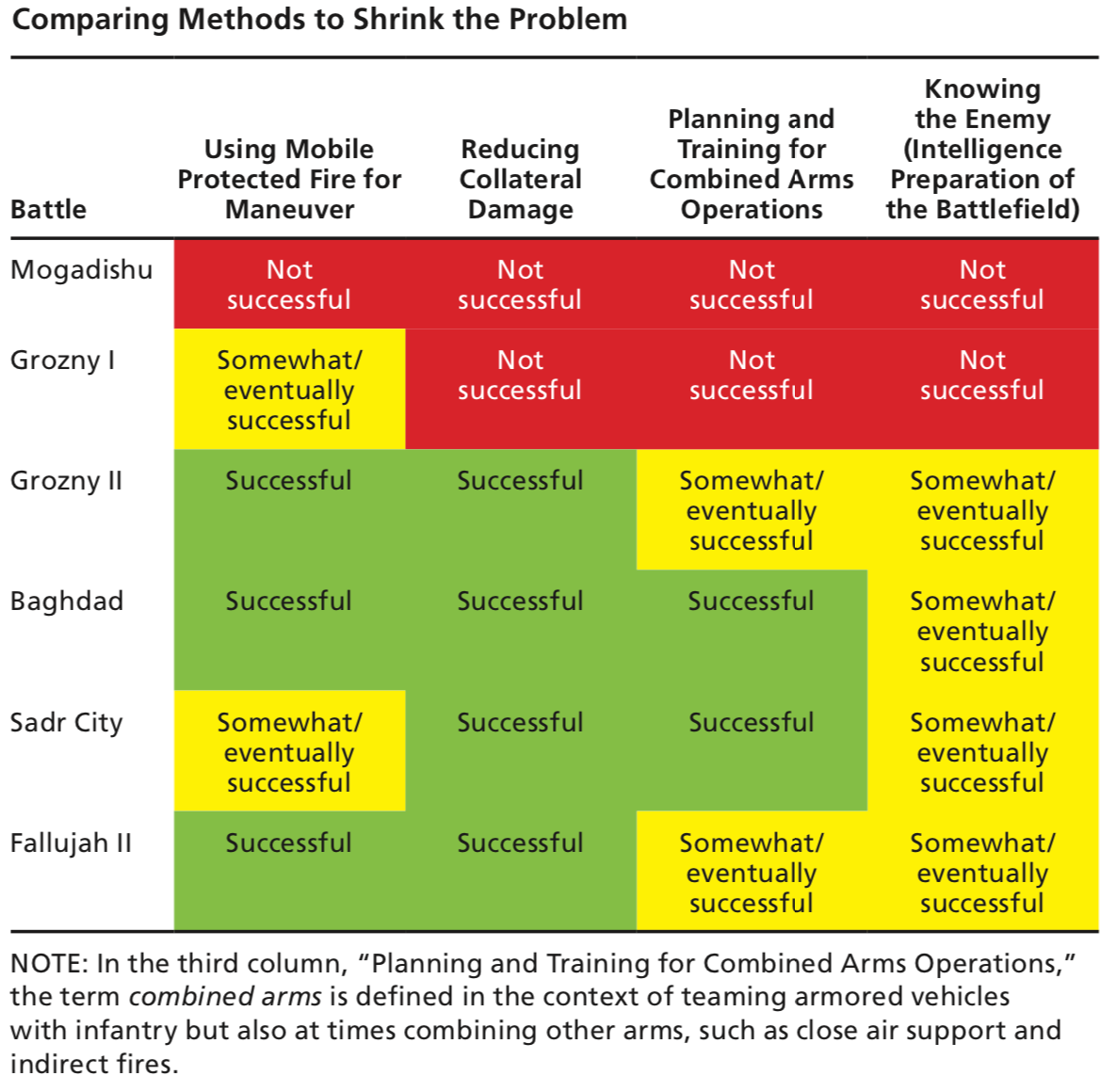

Probably the most interesting of all the analyses and surveys I’ve seen is the RAND Corporation’s Reimagining the Character of Urban Operations for the U.S. Army from 2017. The study looks at 6 different sets of urban operations from Mogadishu and Grozny (I and II) from the 1990s, to Baghdad, Sadr City and the Second Battle of Fallujah more recently. The RAND authors focus on 4 different areas of performance including the use of armored vehicles, the minimization of collateral damage, using air, artillery and ground approaches together, as well as making the most of intelligence.

The most instructive of all these cases - as well as the only one that’s not focused on US action - is Grozny. Russian forces were defeated there by Chechen rebels in 1995 and returned 4 years later to a well-entrenched and experienced enemy. The rebels had been successful the first time around by being extremely mobile on foot, engaging Russian forces very closely to avoid being targeted by artillery, and by drawing Russian soldiers out into the open where they could be targeted by snipers. Having learned their lesson, when Russian forces came back they built their intelligence picture of the city before going in (including the subsurface utility and sewer tunnels), laid siege to the city (essentially sealing it off to all traffic coming in or out), and used Chechen loyalists and “storm teams” to target specific parts of the city one by one - gradually picking apart the rebel forces over time. Instead of trying to cover the entire city with a 6,000-man force, they shrunk the problem down to one neighborhood at a time while keeping a high-level handle on the larger city. They kept tanks out of the city and used them only where they could be protected and supported by infantry on foot. The Russians finally outlasted their Chechen adversaries by keeping a reserve force nearby and rotated rested and freshly trained troops in continuously while the exhausted and isolated rebels were trapped inside.

Just the thought of conflict in a megacity is painful - the complexity, confusion and overwhelming nature of urban life pushed to its limits is hard to picture. Today, success in a future megacity conflict looks like it will lie in the ability to understand and exploit many different but interconnected systems that make a megacity run. Simply finding your adversary and shooting him won’t get you victory - but gaining and keeping the support of the population while pursuing and isolating him might help - so finding ways to be smart about the problem will be key. It’s clear, though, that modern armies need to modify the way they approach conflict, and how they prepare themselves with training and equipment, if they want to be successful. (BJM)

*****

BOOK REVIEW: Murphy’s Law by KS Anthony

KS here.While military memoirs have always held a niche in literature, they haven't really had the kind of popularity that they have now. Beyond the incalculable human cost, two decades of ceaseless conflict in Afghanistan and beyond have given rise to innumerable memoirs, biographies, leadership guides, fitness manuals, and other books that routinely make their way to the New York Times bestseller list. Some are better than others: Among the very good, Ranger Nicholas Irving's autobiography The Reaper, comes to mind, as does former Navy SEAL - I'll put aside the tired jokes about tridents coming with book deals for now - David Goggins' Can't Hurt Me. One of the latest additions to this genre is former NEWSREP (formerly SOFREP) Editor-in-Chief Jack Murphy's Murphy's Law: My Journey from Army Ranger and Green Beret to Investigative Journalist.

Before I discuss Murphy's book, I'd be remiss if I did not address some of the criticism the author received in the Special Operations community following the Mali video coverage by SOFREP, which he addresses in his epilogue. I am aware that there are some who might view this review as an endorsement of the author. It isn't. It's a book review. Treat it as such.

Unsurprisingly, Murphy's Law traces the author's life from growing up in a small town to his military service to his time at Columbia University's School of General Studies to his work as a journalist. Each "block," if you will, consists of tableaus: moments that, woven together, offer a glimpse - but only a glimpse - of his experiences. If you're looking for detailed descriptions of feet ground into hamburger through the rigors of the Ranger Indoctrination Program (now RASP) or tips on how to survive SFAS, you won't get it. The former is covered in three pages, the latter gets a chapter. Those particulars are well covered by others elsewhere, so it was something of a relief to not have to read another description of Pineland or the miseries of rucking blisters. Rather than cover those things, Murphy's work contains some tense - and surprising - episodes in which he portrays himself as young and exceptionally fallible, including one where he mistakes an American recon team for an Afghan enemy patrol and shoots a friendly (he survived) in the ensuing ambush. It's not what you'd expect to read in a GWOT autobiography at all and Murphy is unsparing in describing the aftermath. "The one story never told is mine," he writes. "They never make a movie about the guy who commits friendly fire. I had no mentors to guide me, no sweeping narrative to inform me. I was alone to figure out what to do. I had some support, yet, and I will never forget that, but in the end, I was still disgraced." Murphy is similarly unsparing in describing his investigation - as a journalist - of sexual assault in the military and the consequent backlash he received as a result of publicly airing some of these events: "Covering scandals in the military has made me an unpopular individual," Murphy writes, addressing the issue. "People are angrier that a former member of the special operations community writes these things than they are outraged about the illegal activities. It is a bizarre dynamic, one in which we are supposed to maintain omertà." In conclusion, however, Murphy offers no apologies for kicking down those particular doors. "Real soldiers," he writes, "don't run from the truth, even if it's ugly."

Murphy's talents as an autobiographer and novelist exceed his talents in journalism. Perhaps it's due to my own bias - having worked in media for more than a day, I instinctively distrust all-things-news - but the author's laconic tendencies work well in this context, particularly in his criticism of the Army's bureaucracy and its new-found love of corporate approaches to training. The book is by no means perfect: reading about this many different worlds through the layers of lenses established by Murphy's experiences come close to causing whiplash at times, and I was frustrated by the valorization of journalism, though, again, I have my own cynical biases. What becomes clear at the end of Murphy's Law is that the book is, at its core, less a "war bio" (although there's no shortage of Oakley sunglasses) than a modern bildungsroman: a coming-of-age narrative. "Special Forces is who I was," he says in the book's final chapter, perhaps anticipating his critics' response to his writing this book. "not who I am." (KSA)

*****

TOWARDS QUIET PROFESSIONALISM: Stuff I've Learned - Part 1 (5 min) “Tim Ferris started the “Life Hack” movement with his book, the “4-Hour Work Week.” I remember reading his book when it was all the rage, and wondering to myself if I was the only one who thought a man who sold private-labeled nutritional supplements (a dirty business) for a living and cheated his way to winning a Tango dancing and sumo wrestling contest, was a douche bag. Life hacks, and short cuts in work, relationships, nutrition, fitness, education, etc. are distracting dead ends. The quicker you stop looking for short cuts, and get to work, the sooner you’ll find fulfillment.” (BJM)

PUSHING FOR THOUGHTFUL ADOPTION: Big Tech’s ‘Innovations’ That Aren’t (3 min) “What “innovation” remains in this space is innovation to keep the treadmill running, longer and faster, drawing more data from users to bombard us with more ads for more stuff. But here’s the problem. As we spend more time on that digital treadmill, our real-world relationships atrophy, sometimes to disastrous effect. Teen suicide is up. Twenty-two percent of millennials report that they have no friends. More than a few researchers have noticed a connection.” (BJM)

GREEN BERETS CONTINUE TO SACRIFICE: Third US service member killed in Afghanistan in just over a week (1 min) There have now been 18 U.S. service members killed in Afghanistan this year, 15 of them in combat-related incidents -- the highest number recorded by the Defense Department since 2014. On Aug. 21, two U.S. Army Green Berets were killed during combat operations in Faryab Province in northern Afghanistan. Master Sgt. Luis F. Deleon-Figueroa, 31, and Master Sgt. Jose J. Gonzalez, 35, were assigned to the 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) based at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. (BJM)

Remarks Complete. Nothing Follows.

KS Anthony (KSA) & Brady Moore (BJM)